We Dubois Gifted Liberal Arts Group Was Referedd to as the ?

The Talented 10th is a term that designated a leadership form of African Americans in the early 20th century. The term was created by White Northern philanthropists, then publicized by Westward. Eastward. B. Du Bois in an influential essay of the same name, which he published in September 1903. It appeared in The Negro Problem, a collection of essays written by leading African Americans.[1]

Historical context [edit]

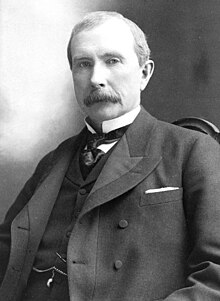

John D. Rockefeller funded the ABHMS, which promoted "Talented Tenth" ideology

The phrase "talented 10th" originated in 1896 among White Northern liberals, specifically the American Baptist Habitation Mission Social club, a Christian missionary society strongly supported past John D. Rockefeller. They had the goal of establishing Blackness colleges in the Due south to train Black teachers and elites. In 1903, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote The Talented Tenth; Theodore Roosevelt was president of the United States and industrialization was skyrocketing. Du Bois thought information technology a expert fourth dimension for African Americans to accelerate their positions in society.[2]

The "Talented Tenth" refers to the 1 in x Black men that have cultivated the ability to become leaders of the Black community by acquiring a college education, writing books, and becoming directly involved in social change. In The Talented 10th, Du Bois argues that these college educated African American men should cede their personal interests and apply their education to atomic number 82 and better the Black community.[3]

He strongly believed that the Blackness community needed a classical education to reach their full potential, rather than the industrial education promoted by the Atlanta compromise, endorsed past Booker T. Washington and some White philanthropists. He saw classical teaching every bit the pathway to bettering the Black community and as a ground for what, in the 20th century, would be known as public intellectuals:

Men nosotros shall take only every bit we make manhood the object of the piece of work of the schools — intelligence, wide sympathy, knowledge of the earth that was and is, and of the relation of men to it — this is the curriculum of that Higher Instruction which must underlie true life. On this foundation we may build staff of life winning, the skill of hand and quickness of brain, with never a fear lest the kid and man fault the means of living for the object of life.[four]

In his later life, Du Bois came to believe that leadership could ascend on many levels, and grassroots efforts were also important to social change. His stepson David Du Bois tried to publicize those views, writing in 1972: "Dr. Du Bois' conviction that it'south those who suffered most and have the least to lose that we should look to for our steadfast, dependable and uncompromising leadership."[5]

Du Bois writes in his Talented 10th essay that

The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its infrequent men. The problem of pedagogy, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the Best of this race that they may guide the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst.

Later in Sunset of Dawn, a collection of his writings, Du Bois redefines this notion, acknowledging contributions by other men. He writes that "my own panacea of an earlier 24-hour interval was a flight of grade from mass through the development of the Talented Tenth; but the ability of this aristocracy of talent was to prevarication in its noesis and character, not in its wealth."

Du Bois and betterment [edit]

W.E.B. Du Bois believed that college educated African Americans should set their personal interests aside and use their pedagogy to better their communities. Using pedagogy to better the African American community meant many things for Du Bois. For one, he believed that the "Talented Tenth" should seek to larn elite roles in politics. Past doing and then, Blackness communities could have representation in government. Representation in government would allow these higher educated African Americans to take "racial action."[6]

That is, Du Bois believed that segregation was a problem that needed to be dealt with, and having African Americans in politics would start the procedure of dealing with that problem. Moving on, he also believed that an education would allow one to pursue business endeavors that would amend the economic welfare of Blackness communities. According to Du Bois, success in business concern would not only better the economical welfare of Blackness communities, it would as well encourage White people to see Blackness people every bit more equal to them, and thus encourage integration and let African Americans to enter the mainstream business organization world.[6]

Conceptual revision [edit]

In 1948, W.E.B. Du Bois revised his "Talented Tenth" thesis into the "Guiding Hundredth."[vii] This revision was an endeavour to democratize the thesis by forming alliances and friendships with other minority groups that also sought to ameliorate their weather condition in society. Whereas the "Talented 10th" only pointed out problems African Americans were facing in their communities, the "Guiding Hundredth" would be open up to mending the problems other minority groups were encountering too.[7] Moreover, Du Bois revised this theory to stress the importance of morality. He wanted the people leading these communities to take values synonymous with altruism and selflessness. Thus, when it came to who would be leading these communities, Du Bois placed morality above educational activity.[vii]

The "Guiding Hundredth" challenged the proposition that the conservancy of African Americans should be left to a select few. Information technology reimagined the concept of black leadership from "The Talented Tenth" past combining racial, cultural, political, and economical ideologies.[viii] Without much success, Du Bois tried to go on the idea of pedagogy effectually. Taking on a new approach of instruction being a gateway to new opportunities for all people. Even so, it was viewed as a stride in the wrong management, a threat of reverting to the sometime means of thinking, and continued to promote elitism.[8] This revision while also being an attempt at democratization of the original thesis, was as well Du Bois' endeavour at creating a program for African Americans to follow later on the war. A mode to strengthen their "ideological conscience."[8]

Du Bois emphasized forming alliances with other minority groups considering information technology helped promote equality amid all blacks.[viii] Both "The Talented 10th" and "The Guiding Hundredth" exhibit the thought that a plan to for political action would need to be evident in society to go along to speak to big populations of black people. Because to Du Bois, black people's ability to limited themselves in politics was the image of black cultural expression.[8] To proceeds emancipation was to carve up black and White. The cultures could non combine as a style to avoid and protect the spirit of "the universal blackness."[8]

Contemporary interpretations [edit]

The concept of the "Talented Tenth" and the responsibilities assigned to information technology by Du Bois have been received both positively and negatively by contemporary critics. Positively, some argue that current generations of college-educated African Americans abide past Du Bois' prescriptions by sacrificing their personal interests to pb and better their communities.[7] This, in turn, leads to an "uplift" of those in the Black customs. On the other paw, some fence that current generations of higher educated African Americans should not abide past Du Bois' prescriptions, and should indeed pursue their own private interest. That is, they believe that college-educated African Americans are non responsible for bettering their communities, whereas Du Bois thinks that they are.[ii]

Advocates of Du Bois' prescriptions explain that key characteristics of the "Talented Tenth" take changed since Du Bois was alive. Ane author writes, "The potential Talented 10th of today is a 'me generation,' not the 'we generation' of the past."[ii] That is, the Talented Tenth of today focuses more on its own interests equally opposed to the general interests of its racial community. Advocates of Du Bois' ethics believe that African Americans accept lost sight of the importance of uplifting their communities. Rather, they have pursued their own interests and now dwell in the fruits of their "financial gain and strivings."[two] Although the percentage of college-educated African Americans has gone up, it is nevertheless far less than the percentage of college-educated White Americans.[2] Therefore, these advocates believe that modern-day members of the "Talented 10th" should still bear responsibility to use their education to assistance the African American customs, which continues to suffer the effects of racial discrimination.

In dissimilarity, those non in favor of Du Bois' prescriptions believe that African Americans have the right to pursue their own interests. Feminist critics specifically, and critics of Du Bois in full general, tend to believe that marginalized groups are often "put in boxes" and are expected to either remain inside those constructs or abide by their stereotypes. These critics believe that what an African American decides to do with their higher education should not become a stereotype either. Furthermore, many of Du Bois' original texts, including The Talented Tenth, receive feminist criticism for exclusively using the give-and-take "man", as if only African American men could seek out a college educational activity. According to these feminists, this acts to perpetuate the persistence of a civilisation that only encourages or allows men to pursue higher education.[ii]

Attainability [edit]

To be a part of this "Talented Tenth," an African American must exist higher educated. This is a qualification that many view as unattainable for many members of the African American community because the percentage of African Americans in college is much lower than the percentage of White people in higher. There are multiple explanations for this fact.

Some argue that this disparity is the result of government policies. For case, financial aid for college students in low income families decreased in the 1980s because issues regarding budgetary inequality began to be perceived as problems of the by.[9] A lack of financial aid can deter or disable one from pursuing college pedagogy. Thus, since Black and African American families brand up virtually 2.9 one thousand thousand of the low income families in the U.S., members of the Blackness community surely encounter this problem.[10]

Moreover, because African Americans make upward such a large number of the depression income families in the U.S., many African Americans face the trouble of their children existence placed in poorly funded public schools. Considering poor funding often leads to poor instruction, getting into college will exist more difficult for students. Along with a poor didactics, these schools frequently lack resource that can prepare students for college. For case, schools with poor funding do not have college guidance counselors: a resource that many private and well funded public schools have.[11]

Therefore, some contend that Du Bois' prescription or programme for this "Talented Tenth" are unattainable.

Run into as well [edit]

- African-American upper course – Contemporary successors of the Talented Tenth.

- Negro University – Scholarly institute that published many works of the Talented 10th.

References [edit]

- ^ Booker T. Washington, et al., The Negro Problem: a series of articles by representative American Negroes of today, New York: James Pott and Company, 1903

- ^ a b c d eastward f Male monarch, 50'Monique (2013). "The Relevance and Redefining of Du Bois'due south Talented Tenth: Two Centuries Later". Papers & Publications: Interdisciplinary Periodical of Undergraduate Research. 2: 7 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Battle, Juan; Wright, Earl (2002). "West.Eastward.B. Du Bois's Talented Tenth: A Quantitative Assessment". Journal of Black Studies. 32 (vi): 654–672. doi:ten.1177/00234702032006002. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 3180968. S2CID 143962872.

- ^ West.E.B. Du Bois, "The Talented 10th" (text), Sep 1903, TeachingAmericanHistory.org, Ashland Academy, accessed iii Sep 2008

- ^ Joy James, Transcending the Talented 10th: Black Leaders and American Intellectuals, New York: Routledge, 1997

- ^ a b Gooding-Williams, Robert (2020), "W.E.B. Du Bois", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Bound 2020 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2020-11-24

- ^ a b c d Rabaka, Reiland (2003). "Due west. E. B. Du Bois'southward Evolving Africana Philosophy of Pedagogy". Journal of Black Studies. 33 (four): 399–449. doi:10.1177/0021934702250021. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 3180873. S2CID 144101148.

- ^ a b c d e f Jucan, Marius (2012-12-01). ""The Tenth Talented" v. "The Hundredth Talented": Westward. E .B. Du Bois'southward Two Versions on the Leadership of the African American Community in the 20th Century". American, British and Canadian Studies. 19 (2012): 27–44. doi:ten.2478/abcsj-2013-0002.

- ^ Carnoy, Martin (1994). "Why Aren't more African Americans Going to College?". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (six): 66–69. doi:10.2307/2962468. ISSN 1077-3711. JSTOR 2962468.

- ^ DuBois, Due west.E.B. (1903). The Talented Tenth. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Brownstein, Janie Boschma, Ronald (2016-02-29). "Students of Color Are Much More Probable to Nourish Schools Where Most of Their Peers Are Poor". The Atlantic . Retrieved 2020-11-24 .

Farther reading [edit]

- The Negro Trouble, New York: James Pott and Company, 1903

- W. East. B. Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn, "Writings," (Library of America, 1986), p 842

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Talented_Tenth

0 Response to "We Dubois Gifted Liberal Arts Group Was Referedd to as the ?"

Post a Comment